Sonja Jessup

BBC London Home affairs correspondent

BBC

BBC

Young people at the Voyage youth charity said the Child Q case had left them feeling unsafe

"I thought, if it could happen to a girl, that is younger than me, imagine what could happen to me?"

It's more than four years since a 15-year-old girl, identified only as Child Q, was strip-searched by police officers at her school in Hackney, east London, after teachers wrongly accused her of carrying cannabis.

The case led to public protests in east London in March 2022, after details came to light in a safeguarding report, which found the search was unjustified and racism was "likely" to have been a factor.

A disciplinary hearing for the officers involved found that race was not a factor in the way Child Q was treated however the Met has acknowledged the incident has affected its relationship with black communities.

Adnan, 18, said it made him feel less safe, "especially as a girl should be safer than me as a boy" and to start to worry about how police officers might look at him with suspicion.

"Now I have to question how I walk, how I dress," he explains.

On Thursday, two Metropolitan Police officers who conducted the strip-search were sacked after they were found to have committed gross misconduct.

Misconduct was proven in the case of a third police officer.

Although the Met's disciplinary panel heard black schoolchildren were more likely to be treated as older and less vulnerable than their white peers, neither age or race were found to be a factor in the way Child Q was treated.

The panel heard that black people were disproportionately more likely to be stopped and searched by police however, the panel did not accept an "inference" that the girl's race caused "less favourable treatment".

Despite this, the Met apologised for "the damage this incident caused to the trust and confidence black communities across London have in our officers".

Commander Kevin Southworth said the force recognised there had been organisational failings, and the incident had brought about a series of changes such as ensuring any searches where intimate parts of the body were exposed was authorised by an inspector, and an appropriate adult must be present.

The force added that it "continued to listen to communities and partners on what more we need to do around our processes" and that it would "continue to work closely with schools".

'Are the police against us?'

Adnan tells me some of his friends took part in the protests and that it had brought the community together, demanding answers from the Met.

"But I feel like we shouldn't have to do all of that, since [officers] are supposed to make us feel protected, instead of threatened."

"It just made me think, is the police against us, or with us?" agrees 18-year-old Prince.

The teenagers, along with Alyssia, 17, Edem, 17, and Tosin, 20, are all ambassadors for Voyage, which describes itself as a social justice charity tackling racial imbalance in London.

Alyssia said she worried for vulnerable children who may not know what their rights are

"I don't think this would've happened to a white girl from a grammar school," Alyssia tells me.

"It made me think, 'how do teachers see me? How do teachers see my friends? Could this happen to me?' And it made me feel really scared."

"I feel like her rights were stripped from her when police did that," Edem says, referring to the search.

"They're supposed to be an extreme measure," adds Alyssia. "There's so many other things they could've done for that girl, whereas that was their first resort and I just don't understand why."

Last year a national report from the children's commissioner on the number of children strip searched raised concerns but found there had been a "sharp reduction" in London which suggested that "some efforts to address the issue are having an impact".

She said the case made her fearful for her own safety and for her younger brother, and that she worried about vulnerable children "who might not know what their rights are".

I ask whether she and her friends and family talk about what to do if they are stopped by police.

She tells me she does, because she feels she has a "duty to protect" her younger brother.

"But I think it's sad that we even have to be having a conversation about this, because it should be the police that's changing, not us."

Prince said he had been left confused over why he was stopped and searched and questioned whether it was because of his appearance

Prince tells me that he was stopped and searched a couple of years ago, on his way home from study club. It left him upset and confused.

"My record is clean and I've never done anything bad to be in the books of police or anything, so, like the way they treated me wasn't really right.

"It made me feel a type of way about it - is it because I'm black? Is it because of the way I look? Is it because I've got dreads?

"I still think about it."

Tosin says he's never been stopped and searched but says he's had police "follow" him and his friends and questions whether he's been racially profiled.

"If you look at me right now, I have twists, I have earrings. People might think I come from a bad background, but I actually come from a pretty good background."

What does he think the solution is to improving trust between police and young people?

"I think as long as the police just communicate with people, and really engage with ethnic minorities, we can have a good relationship."

Adnan agrees that police need to be based, long term, in their local community, so they get to know the Londoners they are protecting.

Edem adds that it's also important the Met recruits officers from diverse backgrounds who reflect those communities.

Through Voyage he's been introduced to a couple of officers in the Met Black Police Association who he "trusts already".

"The way they connected with me, the way they were from the same communities that I was from, it showed that they cared about progress and how to keep everyone safe."

In recent years, the Met has launched a recruitment drive to try and attract women, black people and ethnic minority communities to increase diversity in its workforce.

Tosin and Adnan agreed police needed to do more to get to know their local community

Former Met Det Supt Shabnam Chaudhri told me what happened to Child Q was "unacceptable on every level."

"Young people do need to be stopped and searched. They get used regularly as carriers of firearms, drugs, cash, all sorts of things, but [police] need to manage it in a better way."

Earlier this year, the Met introduced a new set of commitments on stop and search, following consultation with communities across London, including young people.

The force has previously said it's changed its policy on strip searches on children to balance the need for them against the impact they can have, recognising some may be a victim of exploitation by those involved in gangs.

It says as well as requiring an appropriate adult to be present, an inspector must now give authority before this type of search takes place.

Last year, the Met launched a Race Action Plan to try and rebuild trust with London's black communities.

But when I put this to Adnan, who says he has been involved in some of the consultations, he is not convinced.

"Some sessions I went to, it felt like the police officers didn't even want to be there, and it felt like another chore they didn't want to do."

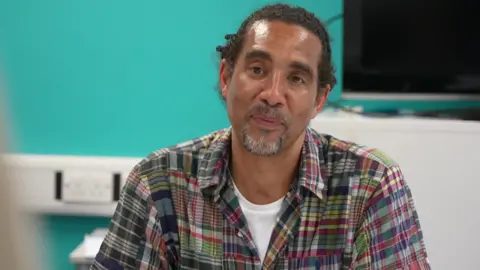

Paul Anderson, CEO of Voyage, tells me there is "no shortage of people" wanting to question their young members about their views to inform policy, but he's yet to see meaningful action.

"We can talk till the cows come home, but actually we want to see change happen, and we're just not seeing that happen."

Paul Anderson, CEO of Voyage, called on police to be more open and transparent with community groups

He says it was partly his own "brutal" experience of being searched by police when growing up in the 1980s which led him to create the group and share his story with younger generations.

But he's frustrated that years later, they're still having the same conversations.

He said police need to practice openness and transparency, including talking to groups like theirs when a young person is stabbed in the area, and when extra stop and search powers, known as section 60, are being put in place.

"Information like that is a bolt of lightening to us," he tells me. "So we can inform the young people to 'be on your Ps and Qs, dress smart, walk well, stay in safe spaces, stay seen."

But he says that doesn't happen.

"It's that sort of catching out of the community, more than us seeing that support to bridge that gap between young people and the police."

He also tells me about how he's tried to gain clarity on whether officers will have a role in local schools.

Last September, an overhaul of Safer Schools Officers (SSOs) was announced in Hackney, meaning they would now advise on policy, but avoid involvement in non-criminal or minor issues affecting young people in school.

Earlier this year, the Met said they would cut officers from schools across London and move them into neighbourhood policing in a bid to save money, which led some teachers to express concern it would make children less safe.

Although the officers involved in the search of Child Q were not SSOs, Ngozi Fulani, CEO of the Hackney domestic violence charity Sistah Space, says the case illustrated why police should not be in the classroom.

"I would take a guess that those who want police officers in their schools know that there's a very low likelihood of their children ever being discriminated against."

Tosin thinks that having more officers in schools could be a helpful move if they are from ethnic minority backgrounds, but Alyssia believes those roles should be filled by youth workers instead.

She says the voices of young people are often missing in decision making by authorities.

Prince tells me he's not reassured by the Met's promises of reform.

"They'll say something, 'oh yeah, I'm sorry, blah blah blah' but the next couple of months you're hearing something happening with the police doing something bad.

"Come on. You can't keep apologising if you're going to keep doing it."

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·