Reading Time: 5 minutes

This blog is one of a series that illustrates how climate change relates to policy areas covered by each subject committee. This one provides a focus on how climate change relates to health and mental wellbeing.

This is a guest blog, written by an Academic Fellow. As with all guest blogs, what follows are the views of the author and not those of SPICe, or of the Scottish Parliament.

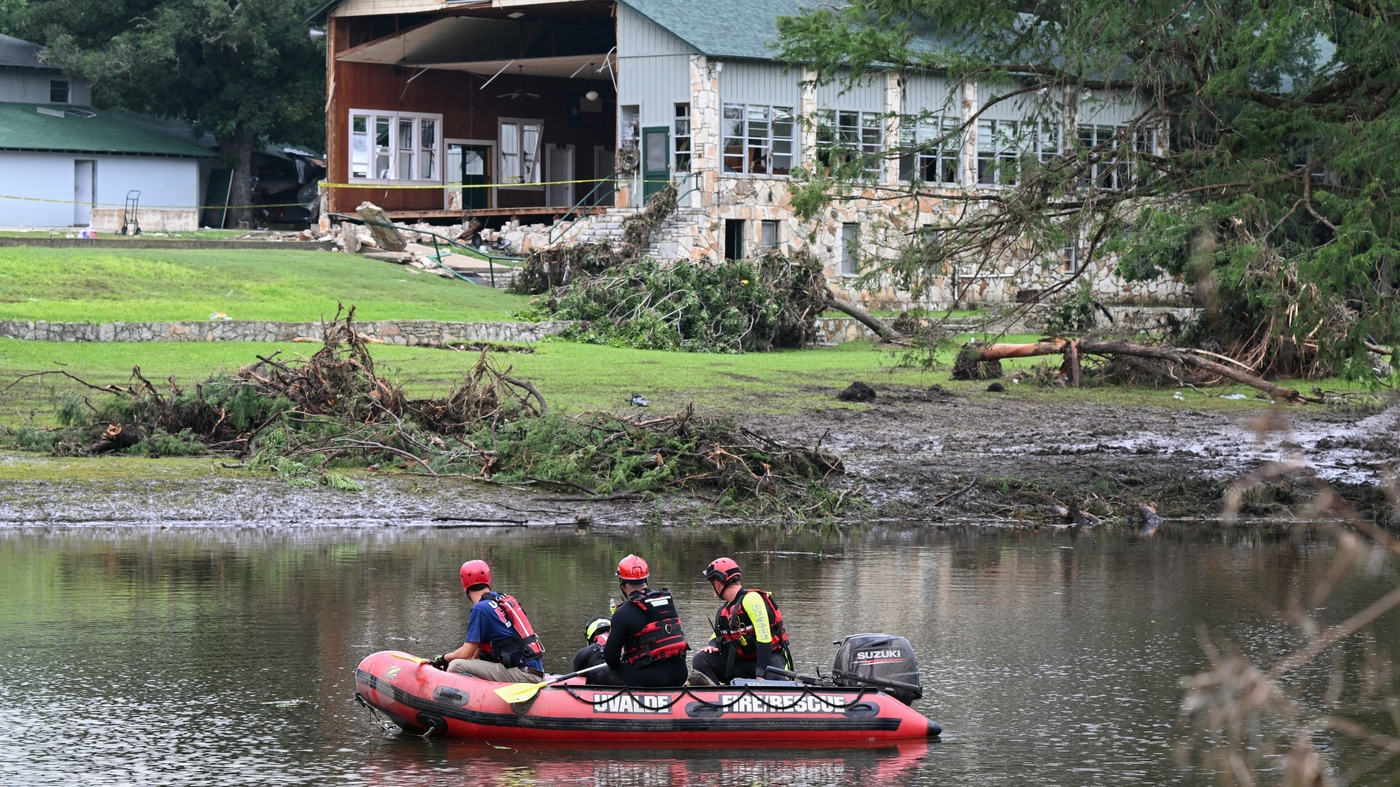

One of the main ways in which climate change can and, increasingly, will affect our lives is through impacts on physical and mental health. As a new SPICe briefing shows, in Scotland, this is likely to include injuries, trauma and stress from events like floods, storms and wildfires; food insecurity caused by drought and increased pests; greater incidences of diseases spread by ticks and mosquitos like Lyme disease; and more deaths caused by extremes of cold and heat. Therefore, acting to prevent worse climate change and preparing for its effects can also help prevent and lessen the impact of the health problems it can cause.

Win-wins

Some people use the term ‘co-benefits’ to describe how climate action can not only reduce the impacts of climate change, but also provide financial, health and social benefits. And this approach need not be limited to climate action, but to policy coherence more generally. Taking a co-benefits approach to health and climate change is a way of preventing the worst effects of climate change and protecting people’s health, which in turn can lead to cost savings for healthcare systems – a win-win-win.

For example, reducing fossil fuel-powered car journeys will have several positive effects. Replacing internal combustion engine cars with electric vehicles will reduce air pollution, which is linked with serious cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Reducing individual car journeys by switching to public transport will also lower emissions, reduce road congestion and lessen particulate matter emissions from brake and tyre wear. But going beyond this and supporting people to walk, wheel and cycle more will have broader physical and mental health benefits by increasing physical exercise; the Health Foundation report that nearly 1,200 early deaths could be prevented through active travel. Changing our roads and streets to accommodate greater active travel can also create greener, safer and more pleasant environments, which can in turn provide health benefits.

Diet is another example where supporting healthier choices could have positive effects for both public health and the environment. Animal-based foods and particularly red meat tend to have higher carbon footprints than other kinds of food. Academics at Harvard Medical School report that diets high in red and processed meat are also associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke and some cancers. Reducing consumption of red meat would therefore have the dual benefit of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and the incidence of some of the leading causes of death in the UK. As noted in the Climate Change Committee report, ‘A reduction in average meat and dairy consumption: this is compatible with a healthy and nutritionally balanced diet and has the potential to bring positive health impacts’. The NHS public- facing websites also recommend reducing or limiting the amount of red and processed meats. NHS Inform, NHS Scotland’s site, bases its advice on the ‘Eatwell Guide’.

Some policymakers worry that asking people to change their diets will be perceived as meddling in personal choices. But it is not necessary to make drastic changes to secure health and climate benefits. In a study published by the British Medical Journal, researchers found that , if the average UK dietary intake were optimised to comply with World Health Organization nutrition recommendations, this could result in a 17% reduction in emissions as well as saving almost 7 million years of life lost prematurely over the next 30 years and increasing average life expectancy by over 8 months.

Joined-up thinking

These examples show not only the importance of recognising the links between climate change and health, but also how we need to think about the effects of climate change across sectors and government departments. Having coherent policies, which consider the effects of climate change and mitigation and adaptation interventions across different remits, can ultimately lead to multiple benefits.

Thinking holistically can also prevent unintended consequences. For example, efforts have understandably been focused on improving insulation and reducing draughts to improve energy efficiency and create warm homes, hospitals and care homes in recent years. But, as the climate continues to warm, we also need to plan for warmer weather and heatwaves, enabling ventilation and natural cooling to prevent over-heating, mould and damp . As a UCL Institute for Health Equity report states, ‘There are significant co-benefits to health from improving the quality and energy efficiency of homes and buildings to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Poor housing quality exacerbates health inequalities and these may widen under conditions of climate change, therefore improvements could help reduce these’.

Caring for planet and people

Shetland GP and Northeast Scotland Greener Practice co-lead Dr Deepa Shah states:

‘The climate crisis is a health crisis. Climate change is already affecting us in Scotland as we see more extreme weather events with storms and flooding, an increase in infectious diseases, and more people seeking refuge from parts of the world that are becoming less habitable. Our healthcare system needs to change to reduce our impact on the environment through lower carbon processes and systems, but also to move to an approach that prevents disease and promotes good health. We need to move away from an industrialised approach to health to one that invests in people and communities to help them to be more active, connected and fulfil their potential.’

Dr Deepa Shah’s comments get at the serious and broad-reaching effects of climate change, but also point us in the direction of how governments might respond positively to this crisis. As she says, if the system isn’t working, governments need to find new tools and new approaches – ones that prioritise the prevention of ill-health in people and protection of the planet.

Scotland’s Chief Medical Officer has similarly sounded the alarm about the effects of the planetary crisis on human health. He argues for centring careful and kind care – looking after the worlds in which we all live, to foster people’s wellbeing and agency without harming the planet on which we depend.

While caring for both the world and people may seem an overwhelming task in the face of climate crisis, it is hardly a wasted effort if it also means improving public health and the environments in which we live.

Dr Katharine Dow, Academic Fellow, Scottish Parliament Information Centre

English (US) ·

English (US) ·