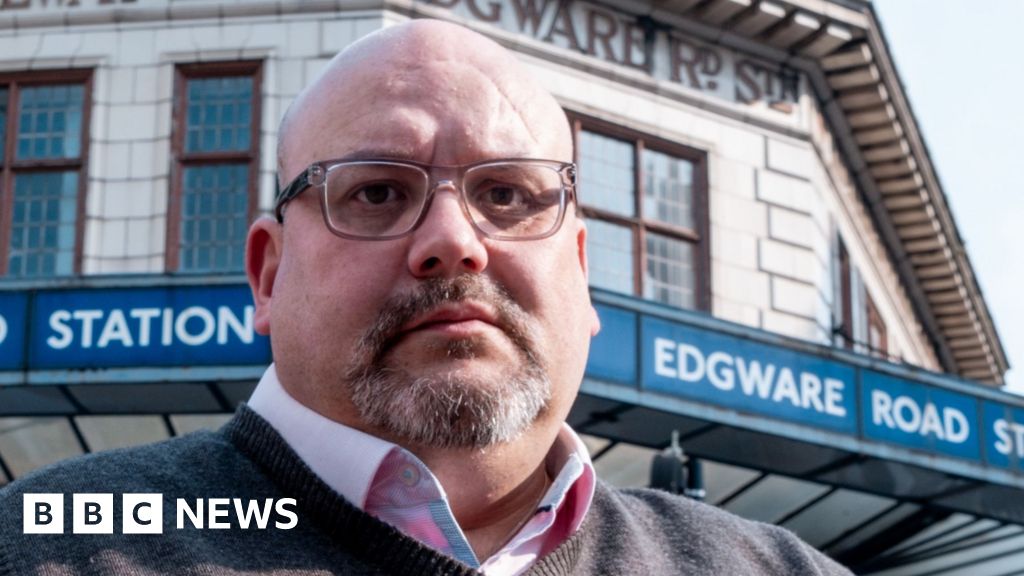

Craig Garfield is a board-certified pediatrician who lives in Evanston with his wife, who is also a board-certified pediatrician. He is a physician-scientist who studies the roles of fathers within families and their impact on child health.

Nearly 30 years ago as a resident, Garfield wanted to take time off after the birth of his first child. He got permission to take two weeks off only after he had banked enough extra shifts to cover his time away. He recalls the same policy applied to the female residents.

“As a dad who wants to be involved with his kid, and as a pediatrician, I really talked the talk with new parents, but hadn’t really walked the walk, right? I would give advice about how to take care of kids, but I had never had a kid,” Garfield said.

A life-changing decision

Eighteen months later when he, his wife and their toddler moved to Evanston, Garfield took a year off from hospital work to be a stay-at-home dad. The impact was unexpectedly life-changing and altered the direction of his career.

His decision to stay home with his child came at an opportune time. He had been accepted to a research fellowship for the following year. He planned to study injury prevention. His wife was about to start training at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago and would be staying overnight at the hospital every third night. They knew it would be a stressful time for their family.

If he was going to stay at home with his child for a year, now was the time.

During his year at home taking care of his child, he became interested in the role of fathers. He wanted to join the local Mom and Tots group, but needed permission from the director. (He got it.) It took six months before one of the mothers quietly told him he’d be welcome to join their local playgroup.

Garfield knew he had advantages as a white, college-educated man, yet he still felt like an outsider. If he was feeling like that, what were other fathers experiencing, he wondered.

Studying fathers and partners

A year later, when he began his research fellowship with the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program at the University of Chicago School of Public Policy, he changed his topic to child health within the family unit, in particular the role of fathers. At Lurie this focus expanded to fathers and/or partners.

Today Garfield is an attending physician at Lurie and a professor of pediatrics (hospital-based medicine) and medical social sciences at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. He started the Family & Child Health Innovations Program (FCHIP) in 2020 at Lurie. Their motto is, “Children thrive when families thrive.” Their focus is the social determinants of health, the role of fathers and how technology can support parenting.

“Social determinants of health” is a catch-all phrase that addresses a series of interconnected, nonmedical factors that affect health. Those factors include socio-economic status, race/ethnicity, education, living conditions, food insecurity, social supports, access to quality health care, community safety and violence, transportation, culture and beliefs.

Measuring milk

At Lurie, Garfield specializes in treating critically ill premature babies in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). He regularly meets with parents to update them about their babies, and even created an app (NICU2HOME) to allow them to see in real time what was going on with their child. He was also on the team that developed a wearable device for mothers that measures how much milk passes to their babies during nursing.

Over time, Garfield observed that most dads lack confidence around their newborns. He learned that many dads assume their partners “automatically” know how to care for the infants. Dads often feel like they are in the way. Garfield said these assumptions occur whether the baby is full-term or a preemie.

“Dads, in particular, the more confidence you can give them, the more likely they are to be involved and feel confident to take care of their baby … Every dad thinks ‘I’m gonna break’ their baby, that they are so fragile, they’re so small. So getting past that only comes with putting in the time so that you get more confident. And it turns out, the more confident you are in the beginning, the more involved you will be later on,” Garfield said.

PRAMS and PRAMS for Dads

There is a lot of data available on pregnant women who receive prenatal care through the PRAMS study. PRAMS is an acronym for Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. Garfield said, “It was funded by the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) from federal appropriations to understand the health and well-being of mothers and their experience in the perinatal period. So pregnancy, through delivery, through three months postpartum. It’s outstanding data, really the gold standard internationally.”

There was only one question in the PRAMS survey about partners. It dealt with whether the women felt safe from violence in their homes. Around 2014 or 2015 someone from the CDC contacted Garfield. He was told, “Women were writing notes in the margins of their PRAMS surveys about the support they were getting from their partners.” There was no way to retain the information. Could he do something to capture this data?

Years of observing dads, working with families and conducting the formative research inspired the FCHIP team to create the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System for Dads (PRAMS for Dads survey). They designed a survey and worked with their colleagues at the CDC to identify states that likely would be receptive to partnering in this research. Georgia was the first state to sign up, followed by Ohio, Michigan, Massachusetts and North Dakota. Maine, Wisconsin and New Jersey plan to roll out their PRAMS for Dads surveys soon. The team’s goal is to sign up 30 PRAMS for Dads states by 2030, hence the catchphrase “30 by 30.”

Research observations

The PRAMS for Dads research began in 2018-2019. Since then the team has published widely based on analyzing the Georgia data, a representative sample of 261 fathers in the state who were surveyed two to six months after the birth of a child (between October 2018 to July 2019).

- Three-quarters or 75% of new fathers surveyed took some parental leave after the birth. The majority or 64% of fathers took less than two weeks of leave after the birth. The main barrier was fear of losing their job.

- When fathers were able to take parental leave, moms tended to breastfeed for longer (measured in weeks). When fathers took at least two weeks of leave from work, the rate of children being breastfed at eight weeks was 31% higher than with those fathers who took less than two weeks of leave.

- Fathers have a strong influence on whether or not mothers breastfeed their children and for how long. When fathers were supportive of breastfeeding, first feeds occurred within the first hour after birth 95% of the time and 78% were still nursing at eight weeks. Among fathers who did not want their partners to breastfeed or had no opinion, 69% reported first feeds within the first hour and only 33% were still nursing at eight weeks.

- Fathers participate in putting their children to sleep, but there needs to be more education for and interaction with fathers about safe sleep practices. Research showed that 99% of fathers put their children to bed, but only 16% followed all three safe practices. Safe sleep practices for infants recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics include placing the child on its back, on an approved sleep surface and in a crib without any soft bedding.

- All fathers, but especially first-time fathers or fathers whose children are in the NICU, should be screened for postpartum depression and other signs of mental stress. Garfield said the research shows “paternal mental health impacts child development and the well-being of an entire family.”

PRAMS impacted by current administration

The Trump Administration shuttered the PRAMS survey on Jan. 31, 2025. An article in the American Journal of Public Health posits that the administration took offense to questions about the gender and sexual orientation of the parents, racial discrimination and “other social drivers of health.”

Garfield wrote in an email, “We actually work really, really hard to be as inclusive as possible including reaching out to the 40% of couples that are unmarried and as a result dad (or the non-birth partner) has really poor birth certificate data.”

The PRAMS for Dads survey will continue. For now Garfield’s team will focus on identifying “philanthropic and foundation support among organizations prioritizing the health and well-being of children and families.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·