Seaside sparrows at Cooks Beach have their own “dialect.” Rowan University researchers monitor their songs as a way to track salt marsh health.

This story is part of the WHYY News Climate Desk, bringing you news and solutions for our changing region.

From the Poconos to the Jersey Shore to the mouth of the Delaware Bay, what do you want to know about climate change? What would you like us to cover? Get in touch.

On an early summer morning, Rowan University professor Gerald Hough and his student Nicolas Buono are standing with microphones at the edge of a South Jersey salt marsh that lies between a dense forest and the Delaware Bay.

Although the busy beach town of Stone Harbor is only about 10 miles east as the crow flies, the only shore sounds you’ll hear are the ubiquitous laughing gulls feasting on the eggs of horseshoe crabs — who are likely the last of the season’s stragglers mating along the beach at high tide.

Dozens of cormorants lounge on top of a collapsed pier. Willets duck and dive among the reeds and high grasses, along with red-winged blackbirds, barn swallows and Forster’s terns.

At the edge of the marsh, Hough and Buono are aiming large microphones at tiny little sparrows perched on the swaying tops of spartina, or cordgrass.

“Welcome to Cooks Beach,” Hough said. “This is probably the closest that you can get to a seaside sparrow in South Jersey.”

Rowan University researcher Gerald Hough studies the dialects of seaside sparrows and how they might tell us when something is wrong in their environment. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Rowan University researcher Gerald Hough studies the dialects of seaside sparrows and how they might tell us when something is wrong in their environment. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

A rare, undeveloped stretch of coastline, Cooks Beach lies about 15 miles north of Cape May Point along the coast of the Delaware Bay.

“We’re looking at these seaside sparrows as an indicator of how healthy the wetland is,” Hough said.

The unique dialect of the Cooks Beach seaside sparrow

For 13 years, Hough and his students have been recording the songs of the seaside sparrow, which summers in the high salt marshes of the New Jersey coast.

Hough and Buono had just spent several weeks camping out at Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge in Delaware, where they say it rained constantly.

“This is definitely the coolest thing I’ve ever done,” said Buono, who studies biology and plans to get a master’s degree in the field. “I’d love to do this again.”

Hough quickly points out the many, little seaside sparrows swaying on the tips of the marsh grass.

“So, the birds that we’re looking for, there’s one right there, you can hear them, it sounds like they’re going, ‘phoebe, phoebe,’” he said.

A seaside sparrow sits in the salt marsh near Cooks Beach in Middle Township, New Jersey. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

A seaside sparrow sits in the salt marsh near Cooks Beach in Middle Township, New Jersey. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The seaside sparrow blends in remarkably, but it does have bright yellow markings between its eyes and beak and a white patch on its neck, visible when it lifts its head to sing. It’s the only sparrow living in the high salt marsh between the beach and the forest.

“The Delaware Bay is somewhat protected compared to the Atlantic Seaboard coastline in that there’s a lot more native marshes here,” Hough said.

Dotted within the marsh’s quicksand-like mud are islands of cordgrass — and that is the perfect place to raise seaside sparrow chicks free from predators. The height of the grass protects the nests from storm surge.

“These guys are all over the place, and you could probably hear them in the background. Their most characteristic feature is they have this buzz at the end of their song that sounds like, ‘beezz beezz,’” he said.

A seaside sparrow sings in the salt marsh near Cooks Beach in Middle Township, New Jersey. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

A seaside sparrow sings in the salt marsh near Cooks Beach in Middle Township, New Jersey. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Hough is interested in the sparrow’s dialect, or what he refers to as an accent.

“Just like we have different accents on different words, so do they. And so, just like we say ‘wooder’ in Philly, they sound the same here,” he said. “They learn song very much like [we learn language], which is why a lot of people study them to learn about language evolution.”

For that reason, Hough’s research could lead to solutions for people who have trouble with language learning.

“When they are little they do babbling very much like humans. We call it sub-song,” he said.

And like humans, Hough said by the time they are adolescents, their dialect is pretty solid.

Hough said the sparrows he has recorded in Connecticut and Delaware, or even down the road from Cooks Beach, have different dialects. But he’s particularly fond of the song of the Cooks Beach seaside sparrow.

“He’s got like a little trill,” Hough said. “He’s got a very long trill before he goes to that end buzz. And that’s something that’s characteristic that we’ve recorded here for quite a while. So some of them have this very, very slow kind of ‘sweet pee pee pee pee pee’ before they get to the buzz. But these guys [at Cooks Beach] have a very rapid kind of ‘bbbbwweee.’”

Rowan University undergraduate research assistant Nicolas Buono records the songs of seaside sparrows at Cooks Beach on the Delaware Bay. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Rowan University undergraduate research assistant Nicolas Buono records the songs of seaside sparrows at Cooks Beach on the Delaware Bay. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Hough said their message is pretty simple — this is mine.

“So, my territory, my area, my resources, my nest, my mate, mine,” he said.

Climate change and the seaside sparrow

Although Hough began recording the seaside sparrow as part of his research into regional dialects, in doing this research, Hough noticed changes that worried him.

“They require a very specific set of habitat characteristics,” Hough said. “They need to have a mix of these low grasses and not the very tall reeds that you see in some other areas.”

He said this type of high salt marsh is only found within 1 mile of the ocean, and that it’s the only habitat that supports the seaside sparrow.

“You won’t find them in the forest, you won’t find them in meadows, and so if anything happens to this vegetation here at Cooks Beach, you’re going to lose the birds,” he said.

The salt marsh at Cooks Beach hosts many seaside sparrows, but it is surrounded by housing developments and threatened by sea level rise. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The salt marsh at Cooks Beach hosts many seaside sparrows, but it is surrounded by housing developments and threatened by sea level rise. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Hough said the birds faithfully return to the land of their birth. So, if he starts to hear other dialects or “accents,” that would raise a red flag.

“If you hear people that have an accent where you don’t expect it, there must be a reason why they left where they used to be — so, same thing for the birds,” Hough said.

Just like the bird itself can be an “indicator species” to warn of issues with the marsh, he said, the dialect of the Cooks Beach seaside sparrow is an indicator of issues with the bird.

“And so, by looking at the song, we are hoping to get some clue as to whether this area is stable, or whether this area is threatened,” he said.

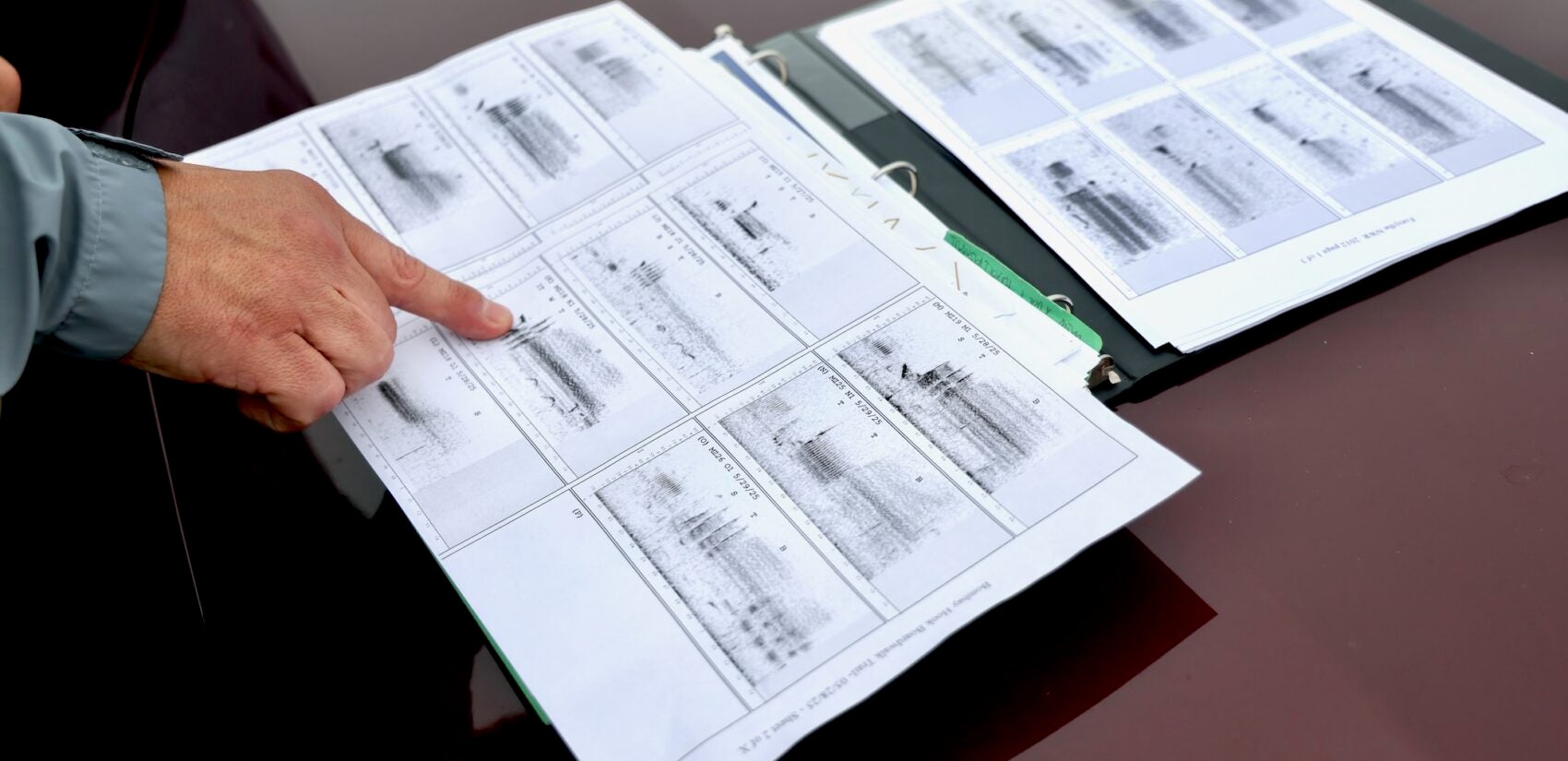

Sonograms, visual representations of sound, are useful in identifying the different dialects among seaside sparrows. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Sonograms, visual representations of sound, are useful in identifying the different dialects among seaside sparrows. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

While the Delaware Bay coast is considered one of the most resilient to withstand sea level rise, Hough said in 40 or 50 years, the marsh could be underwater due to climate change.

So, can these birds move somewhere else?

“If they disappear, then that means that all the plants here that rely on them for seed dispersal and keeping the insects in line, they go away,” he said.

Hough said compared to recordings done over a decade ago, only about 30% of the same songs are still sung at Cooks Beach, but he’s not sure why.

Right now, Cooks Beach is a healthy marsh and he hopes it stays that way. But if the marsh disappears due to climate change, he worries the unique songs of the Cooks Beach seaside sparrow could as well.

A seaside sparrow sings in the salt marsh near Cooks Beach in Middle Township, New Jersey. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

A seaside sparrow sings in the salt marsh near Cooks Beach in Middle Township, New Jersey. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·