This story is part of the WHYY News Climate Desk, bringing you news and solutions for our changing region.

From the Poconos to the Jersey Shore to the mouth of the Delaware Bay, what do you want to know about climate change? What would you like us to cover? Get in touch.

Pavement, black top and dense buildings all contribute to making urban areas hotter than nearby suburbs or rural areas — sometimes driving up temperatures 5 degrees Fahrenheit higher in parts of New Jersey and the Philadelphia area, according to a 2024 analysis by Climate Central. The additional heat from the built environment can be deadly and increases electricity bills, which disproportionately impacts low-income residents.

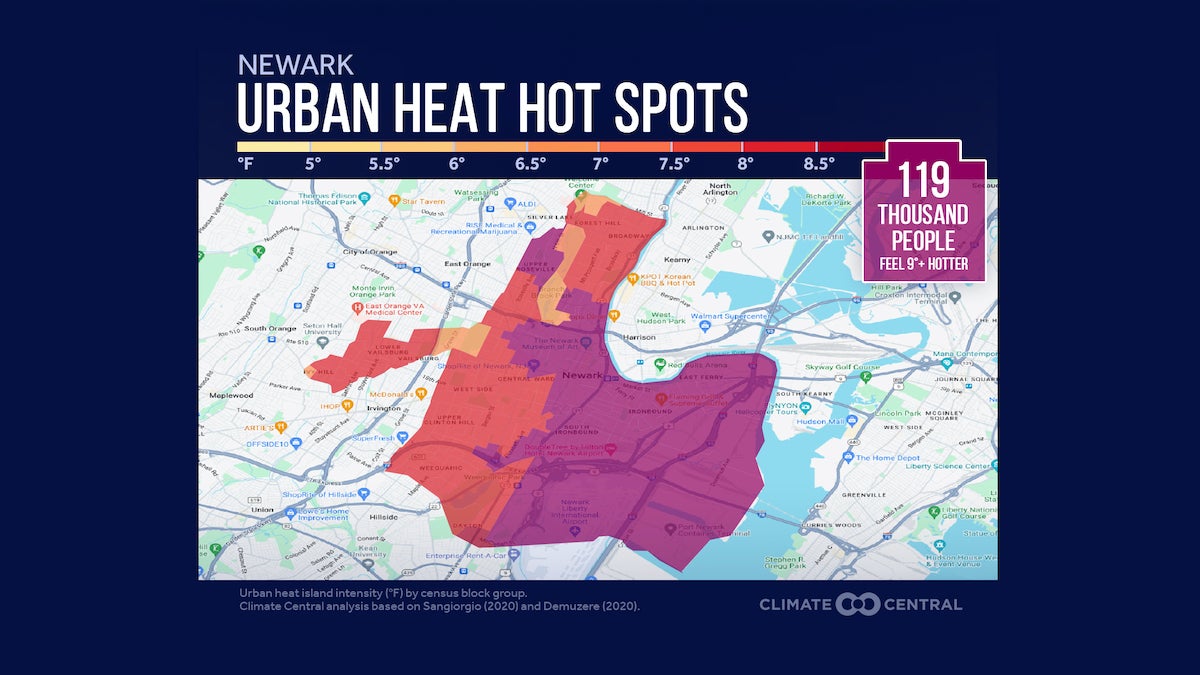

Referred to as the urban heat island effect, Climate Central listed Newark, New Jersey as one of the hotspots, with temperature increases of up to 9 degrees Fahrenheit.

Climate change–related temperature increases are higher in New Jersey on average than in many other states, said Jonathan Gordon, deputy director of Clean Energy Equity at the state’s Board of Public Utilities.

“The average temperatures are just going up faster,” Gordon said. “It has to do with the fact that there’s a lack of shade tree canopy, there’s just more concrete, more asphalt, and that heat gets absorbed and then it releases itself and cools down slower, compared to areas where there’s more green space.”

Graph created by Climate Central showing various heat measurements caused by the urban heat island effect (Courtesy of Climate Central)

Graph created by Climate Central showing various heat measurements caused by the urban heat island effect (Courtesy of Climate Central)

Average summer temperatures in Camden, for example, have risen 3.2 degrees since 1970.

Gordon said summer temperatures are going to continue to rise, especially in cities.

“In Newark, a historical average was 15 to 20 days of 90-degree weather or worse,” Gordon said. “Right now, we’re at 30 or 40 [days]. By 2035, we’re [going to be at] 40 to 60 days of 90-degree weather or worse.”

High heat combined with high humidity is dangerous, Gordon added. That’s because high humidity prevents the body from shedding internal heat through sweating. It also prevents nighttime temperatures from cooling down.

“Not a lot of people realize how deadly heat is,” Gordon said.

As a way to help communities prepare for or mitigate urban heat, the New Jersey Bureau of Public Utilities announced a $5 million grant program.

“Extreme heat doesn’t just threaten our health and safety — it drives energy costs through the roof, hitting hardest in communities already facing intensified heat from the Urban Heat Island effect,” said BPU President Christine Guhl-Sadovy, in a statement. “The NJBPU has a fundamental responsibility to ensure reliable, affordable energy for all New Jerseyans, which means tackling the contributory causes of energy demand.”

The BPU said Camden, Trenton and Newark have some of the highest urban heat island effects, similar to Philadelphia and New York.

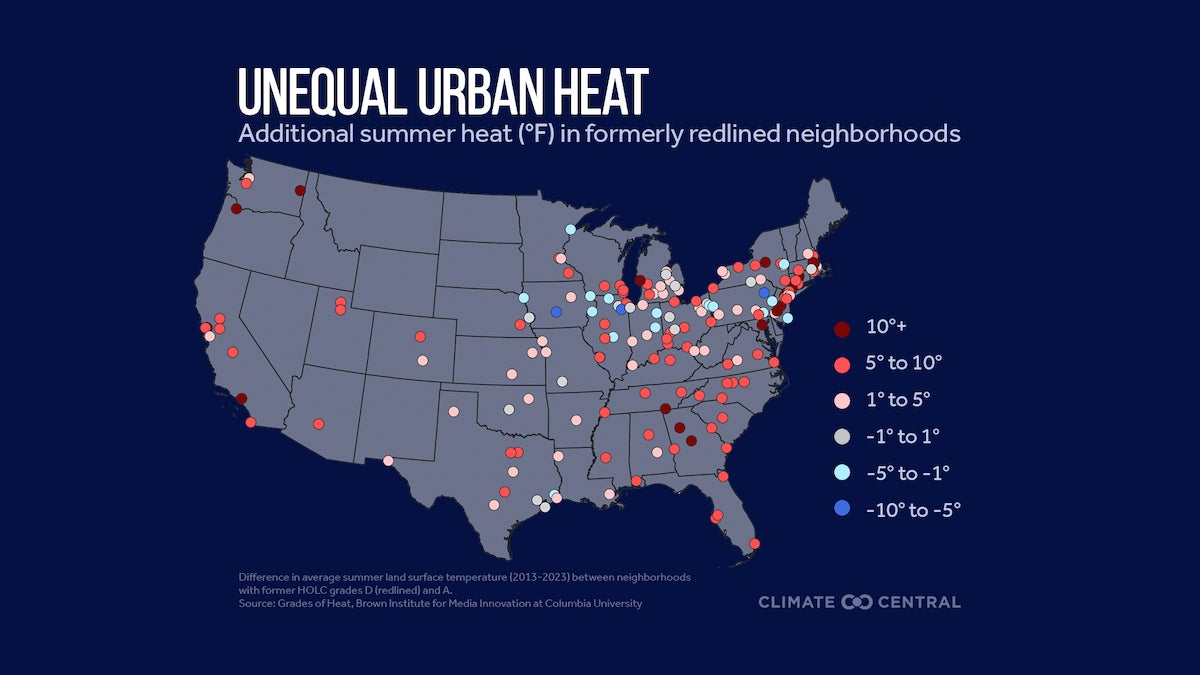

Graph created by Climate Central showing summer heat temperature measurements at formerly redlined neighborhoods and cities across the U.S. (Courtesy of Climate Central)

Graph created by Climate Central showing summer heat temperature measurements at formerly redlined neighborhoods and cities across the U.S. (Courtesy of Climate Central)

Funded by the New Jersey Clean Energy Fund, the grants are broken down into three categories and the projects must be accessible and located on public land: two $1 million dollar awards for major cooling infrastructure projects; four grants to upgrade public buildings for up to $500,000; and 20 $50,000 awards for community-led “micro-climate interventions.”

“So that could be a civic association, that could be a local nonprofit, but it has to … engage with the community,” Gordon said. “The theme through all three of these different grants is that we want to enhance the public space and we want to ensure that communities have greater connections.”

Gordon added that research shows strong community ties lead to greater resiliency in any type of climate-related disaster.

“Heat is very connected in that way, where it could be that those community connections would allow people to possibly know that such and such lives down the street, and can’t physically lift their air conditioner unit into a window,” Gordon said. “And [if] you have more community connections, somebody might be able to offer say, ‘Hey, let me put that in there for you.’”

Graph created by Climate Central showing how different elements of cities affects their overall temperature (Courtesy of Climate Central)

Graph created by Climate Central showing how different elements of cities affects their overall temperature (Courtesy of Climate Central)He said the board is looking for creative solutions that build community over the long term — especially with public spaces.

“How can we ensure that someone can use this public space for more than one hour, more than two hours, three hours, and be able to find a nice, cool, shaded, relaxing place, but also a place where they can build more community connections so that we can build more resilient communities?” Gordon said.

The board will begin taking applications for the grants in September.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·